Sensors are an essential building block of the internet of things. The fact that sensing, wireless power, and computing are all so much cheaper and more available compared with a decade ago has been driving the adoption of IoT for the last five years. But it’s not enough.

If we want to blanket factories, cities, offices, and homes in sensors, we need better batteries — or better battery life. You can’t replace the batteries inside a billion or a trillion sensors in any practical way. To solve this problem, chip companies are trying to create low-power radios and processors. Other companies are investing in energy-harvesting technologies.

Psikick, a six-year-old startup, is doing all three things. It’s building a system of sensors, wireless tech, and energy-harvesting processors to solve the power problem associated with the IoT.

The Psikick sensors don’t require any batteries and can last for up to 20 years. The secret, according to co-founder Ben Calhoun, is that the Psikick team designed everything for a super low-power environment. The company’s sensors harvest their own energy using movement, light, or temperature changes and consume roughly 20 microwatts.

They can gather about 10 microwatts per square centimeter. The idea is that placing the sensors on moving industrial equipment gives them the power they need to transmit data about that equipment. They can also be placed in steam traps, where they can gather data through temperature changes. There are lots of options, but the first product will be a system for tracking data for steam traps in industrial settings.

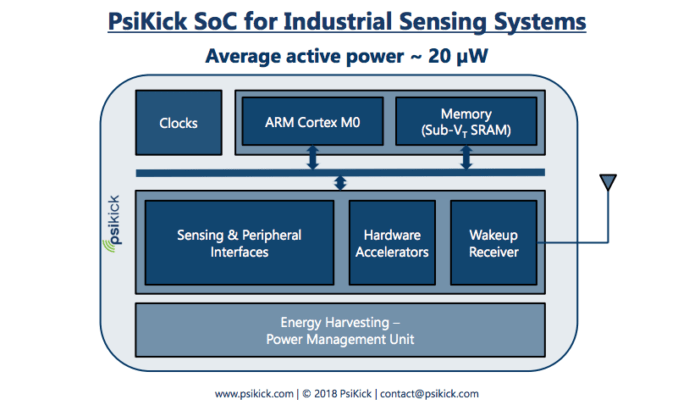

Obviously 10 microwatts is not a lot of power, so the Psikick founders realized they needed to design a different style of computing processor and wireless transmission system to operate under such power constraints. Calhoun says the firm designed several components for a system on a chip optimized to avoid energy waste. These components include voltage converters and a circuit to manage energy flow to the processor.

The processor itself takes advantage of a technique called sub-threshold logic, which lets chips compute at much lower-than-normal power consumption by having them perform their calculations at close to their minimum voltage threshold. Other companies, such as Ambiq Micro, are also exploring this technique. Ambiq has shown chips that have cut power consumption by 10x compared with ARM-based silicon.

On the radio side, the system on a chip Psikick designed has an always-on listening receiver and a separate transceiver to send data. The transceiver will wake up to transmit data, and the lowest-power version of the always-on listening radio runs at 200 nanowatts, says Calhoun. The wireless protocol Psikick engineers designed is proprietary and focuses on energy efficiency and low latency as opposed to sending huge quantities of data.

Psikick didn’t share actual transmission rates or distances, which will be essential elements to consider when thinking about whether or not this will work in your industrial setting. The low transmission rates and limited compute power mean the Psikick sensors can’t gather all types of data in all types of environments.

Calhoun also says that thousands of Psikick sensors can communicate with the gateway device Psikick uses. The implementation would consist of “stamp-like sensors placed everywhere that support a large network.” Psikick has raised an undisclosed amount of funding from NEA.